Featured Music:

[Music]

In August of 2019, my brother Sam got married.

When he called me and asked me to be his best man the year before, I remember joking with him that I would use my speech as an opportunity to talk about this rash I’ve been having, or to go on a rant about how I thought 9/11 was an inside job--which I don’t, by the way. It was a joke; that was the point. But I remember Sam getting real quiet on the phone, and saying, [pause music] “Will, you’d better not do that. Please don’t make me regret this.”

[Resume music]

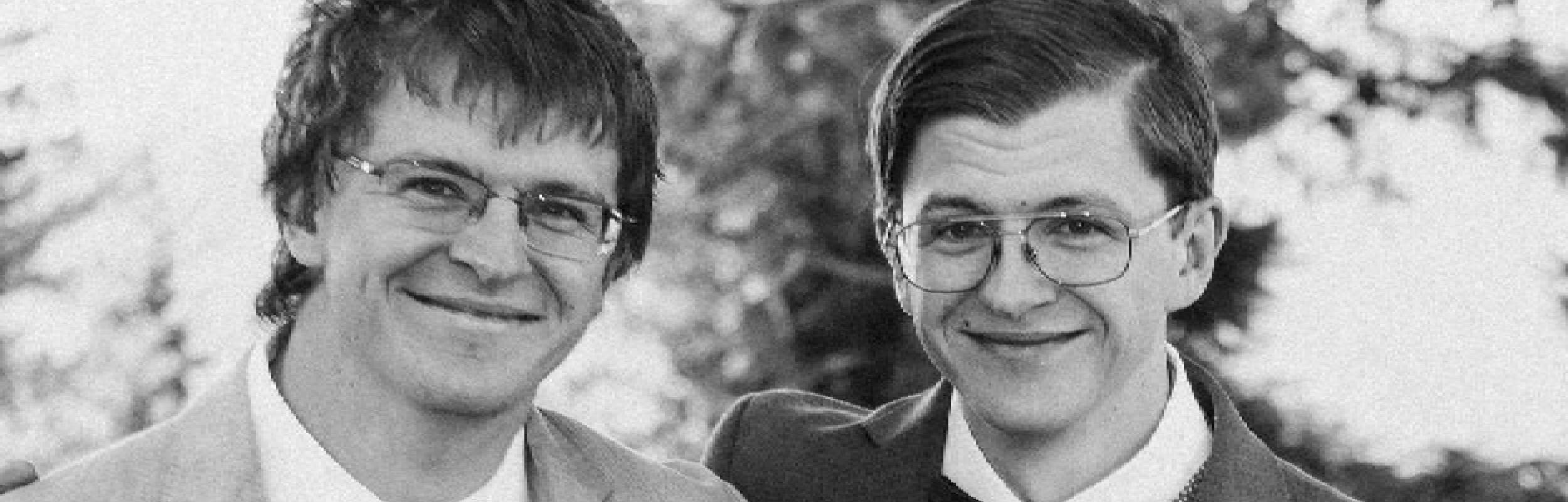

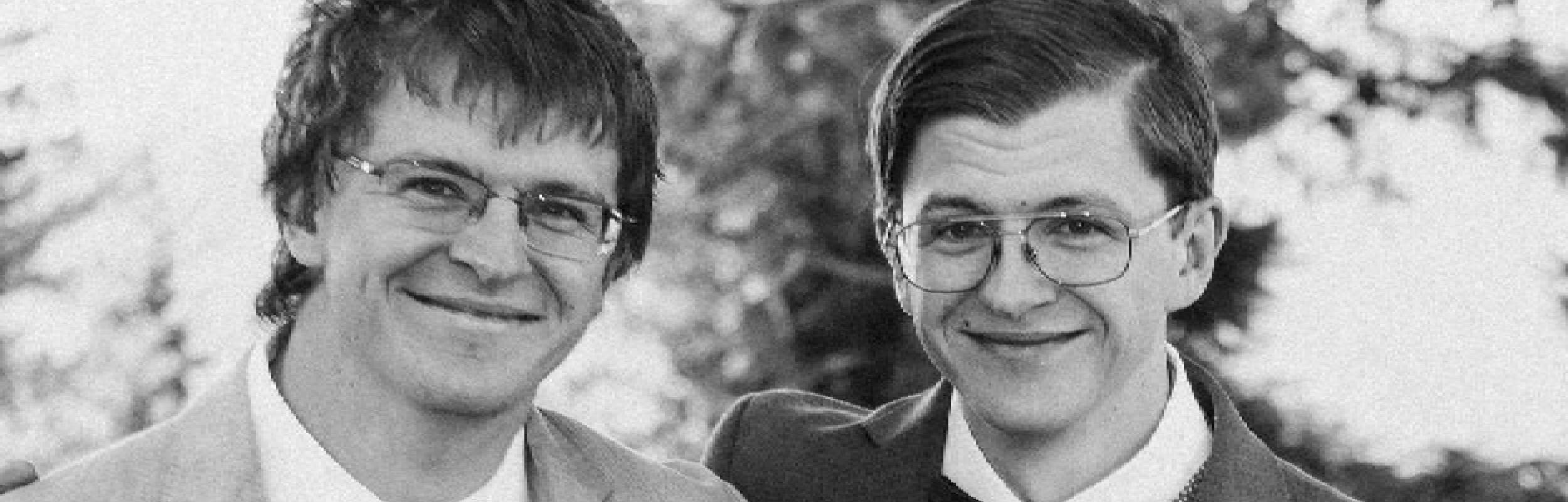

Sam seemed to think that I might not be kidding, that I might actually use my platform as his best man on one of the most important days of his life to humiliate and embarrass him. And I think that highlights a key difference about us: Sam is super serious. And I’m not. Not at all. In fact, I consider myself a real goofball. And that might surprise some people, especially because there is a lot about us that is the same. After all, we’re twins. Identical twins.

So on the day of my brother’s wedding, I didn’t humiliate him--or at least not intentionally. But I did open with a joke. And before I play this for you, I just want to mention one key bit of information for you about my brother’s wedding: my brother’s bride, Jimil, who is now my brother’s wife and my sister-in-law, is also a twin. An identical twin.

[Play audio from 5.31]

[V/O] My brother paid a videographer to document his wedding, which is the only reason I have audio of this. In addition to asking me to be his best man, my brother also asked me to be the MC, so I had to introduce the speakers, make announcements, that sort of thing. I started off by making a few announcements--that folks should be mindful of the wind, to hold onto their champagne until the last toast, to thank Jimil’s dad for raising, slaughtering, and preparing the lamb we were enjoying, for example. I also reminded everyone to tip their bartenders, which I’m really glad I did, because it scored me some free drinks for the remainder of the evening. Anyway, I gave my toast after Yila, Jimil’s twin sister.

The wedding was at a mountain resort called Bogus Basin in Boise, Idaho, where Jimil and Yila grew up. If it sounds like I’m out of breath, it’s partly because we were something like 2 miles above sea level. Picture a warm August afternoon in a giant tent set up on a concrete, which, during other parts of the year, are tennis courts. Also, if it sounds like I’m nervous, it’s because I was.

[Play audio to 8:12 - “Nothin weird about this…”]

The toast goes on. By the way, I should really credit my pal Pete Smith for help with that joke. And why did I ask my friends for help writing this speech? Remember the part where I said that Sam wasn’t able to be the best man at my wedding? [replay clip] Well, that’s because my wife and I decided to elope. It’s kind of a long story, but the punchline is that we got married in 2013 and didn’t tell either one of my brothers or my parents--who were actually out of the country at the time--until after the fact. Oh, and then we did it again in LA for New Year’s a few months later. That’s right; we got married--twice--and somehow I neglected--or forgot--to invite my family both times. We had always said we were going to elope, then do a West coast wedding, and then at some point, an East coast wedding--and we did steps 1 and 2, but we never got around to step three. Needless to say, this was a deep affront for my brother. He felt betrayed. How could I get married and not tell him? I’m still not sure I know the answer. The point is, I asked for help writing this toast because I saw it as a chance to redeem myself--to once and for all make up for the fact that I had neglected to bestow this honor upon my brother--my twin brother. I felt I was under an enormous amount of pressure. So I reached out.

The truth is, I was devastated that my brother felt like I had excluded him from my own marriage ceremony. Aren’t twins supposed to tell each other everything? Aren’t they supposed to know what’s going on with one another without even needing to say it? What about twin language? Did we learn nothing from all those Cheech and Chong movies? So why didn’t I tell him? Or maybe the question is: why couldn’t I tell he would get so upset?

Another thing I mentioned in my toast is that I wanted to dispel some myths about twins--and I do. If you’re a twin, you are probably tired of explaining to people that no, when my twin gets hurt, I can’t feel it. And no, we don’t have some secret language that only we can understand. (My parents like to tell a story about how one time, when my brother and I were still too young to walk, they put us to bed one night in separate cribs on opposite sides of the room, only to find us in the morning in the same crib. I think this could be due to any number of things that my parents probably should have been more concerned about than a cute and inexplicable story--something like a potential break-in or an attempted kidnapping.) Finally, no, we don’t function as stand-ins when we can’t be two places at once. I don’t fill in at the important business meeting so that my brother can still be at his anniversary dinner without letting on to either his wife or his boss that he accidentally overbooked himself. This isn’t a sitcom, and we’re not clones.

Here are a few cold hard facts about twins. Identical twin pregnancies occur about 0.45 percent of the time. 1 in every 250 births is an identical twin (or maybe it’s more accurate to say about 2 out of every 500 births are twins). Identical twins occur when the egg splits after it is fertilized. Identical twins sometimes have the same genetics, but not always. (I’ve often wondered if my brother could frame me for grand theft auto by leaving a drop of his blood inside of a stolen car. When my daughter was born, I found out I’m a carrier for cystic fibrosis. I assume this means he is too, but I can’t be sure unless he gets genetic testing). Identical twins never have the same fingerprints (which means I can’t unlock his iphone and I’ll have to figure out another way to frame him for grand larceny. I’m kidding. [pause music] My brother doesn’t have an iphone.) Apparently, about 40% of twins actually do develop some kind of autonomous language--so I guess I lied earlier.

You might know about the Mowry twins (child stars of Sister Sister), the Olsen twins (child stars of Full House), the Bush sisters, the Winklevoss twins, but did you know that Jon Heder (aka Napoleon Dynamite) also has an identical twin brother? Elvis had a twin brother who died at birth. Apparently, it haunted him.

Fraternal twins are dyzigotic, (which means they are less interesting). But really, dyzigotic meaning they occur when two separate eggs are fertilized. Sometimes this is because more than one egg has been released, which is common in women who have hyperovulation, which can be genetic. So like diarrhea, twins can run in your genes.

Vin Diesel, Alanis Morrissette, Isabella Rossellini, Ashton Kutcher, Kiefer Sutherland, Scarlett Johannsen all have fraternal twin siblings.

But still, isn’t there still something kind of weird about twins? [play clip from game of thrones] Jamie and Circe Lannister from Game of Thrones certainly haven’t helped make twins seem less weird in popular culture (hashtag twincest). When I was 10, my family moved to a house in the suburbs of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. I spent my fifth grade year in a very small elementary school of about 200 students. In my fifth grade class alone, there were five sets of twins. One of them--let’s call them the Williams brothers--were identical twins who still wore the same thing to school every day. They had the same backpacks, the same bikes, the same shoes, and the same outfit, every day. They even had the same initials: Mark and Matt. I know that the parents are likely at fault when something like that happens. I have seen old photos of my brother and me dressed in the same outfit. But in fifth grade?

At my brother’s wedding, I wanted to joke about how twins are weird. And some twins are weird. The chance of giving birth to identical twins might be 2 in 500, but what are the chances of two identical twins marrying one another? And what are the chances of those twins having twins? I don’t know, but I’m sure they’re astronomical.

Nevertheless, it happens.

In August of 1998, Craig and Mark Sanders attended the annual Twins Day Festival held every summer in Twinsburg Ohio. I love how the article by Scott Stump from 2013 puts this: “Mark Sanders had just experienced love at first sight at a twins convention in Twinsburg, Ohio, when his first thought was that he better go find his identical twin brother.” When people say that twins are weird, I think they are talking about this kind of co-dependence. Mark met and fell in love with Darlene Nettemeier, and then introduced his brother Craig to her sister, Diane Nettemeier. The brothers proposed on the same day, and married the Nettemeier twins the following year. Then, in 2001, Diane gave birth to identical twin boys, Colby and Brady.

In the months leading up to their wedding, I sent my soon-to-be sister-in-law articles about the Sanders twins and the Twins Day Festival. I would remind her to keep the weekend of the Twins Day Festival open, because we were going. “Tell Yila,” her sister, I said. Of course, I was not serious. Again, I’m the goofball here, the joker. To clarify, I don’t think my brother’s relationship with Jimil is “weird” or too co-dependent; I actually don’t think the fact that they are twins has anything to do with their relationship. They didn’t meet in Twinsburg Ohio, and I didn’t introduce them. I don’t think of either one of them as co-dependent people. But I also can’t help wondering if that is part of what brought them together. Were they drawn to one another because in some way, they thought, here’s a twin who can stand in for, supplement, or maybe replace my relationship with my twin sibling?

By the way, this is also a question I could be asking of myself as well. While I didn’t marry a twin, my first “girlfriend,” who was also maybe my first kiss, in middle school was a fraternal twin. At the time, I didn’t think twice about whether or not that was strange or was symptomatic of co-dependence. But now it has me wondering.

Today, I’m also less sure that I’m kidding when I say that I want to go to the Twins Day Festival in Twinsburg Ohio. Apparently, twins meeting their twin spouses is not an uncommon occurrence. In August, 2017, identical twins Brittany and Briana Deane met identical twins Josh and Jeremy Salyers (a lot of alliteration with these names, you’ll notice) at the Twins Day Festival. A year later, the two couples married one another at the same event where they met.

So why does this happen? Are twins more co-dependent than other pairs of siblings? Was twinship a factor of any consequence in my brother’s courtship with his wife?

These are all interesting questions, and I would like to get to the bottom of them. But answering these questions is not really my goal with this podcast. Instead, I want to tell you a story that isn’t really mine to tell. It’s a story about my brother that I know my brother could do a better job telling. In fact, it’s a story he’s already told, and has been telling for years now. The trouble is that you haven’t been listening. This is a story about the one moment in my life when I found myself unable to handle being a twin. It’s a moment I’m still reeling from, and a moment I know he is haunted by. But it’s also the moment where I think my twin brother and I finally set off on different paths to become our own people--me, a goofball father who has trouble taking anything too seriously, and him, a serious artist. It’s the story of how my brother and I came to be different people to the point where one of us wants to visit Twinsburg Ohio in August, and the other doesn’t.

My name is Will Steffen. Welcome to Someone Else’s Blues, a podcast about twins, twinship, and the best singer-songwriter you’ve never heard of.

Steven Wright - Wicker Chairs and Gravity 5/7 - 1:00 mark

One of my favorite stand-up comedians, Steven Wright, has this joke:

[audio]“When I have a kid, I want to put him in one of those strollers for twins, then run around the mall looking frantic.” ~Steven Wright

It’s great deadpan humor, classic Steven Wright. But it’s also funny to me because it simulates a loss I don’t think I’m quite capable of imagining.

My brother Sam and I were never really separated until he went off to college. In our junior year of high school, our dad took us to look at some colleges in New England. I was not particularly excited about going to college; I had read a few too many George Orwell novels which had romanticized a working-class lifestyle it turns out I really knew nothing about, so I was more excited to get a job after high school than to try to get into college. But my dad wanted to show us some “alternative” kinds of schools, so he drove us up the New York Thruway to visit Bard College in Annandale on Hudson. From there, we jumped onto the Mass Pike to visit Hampshire College in Amherst.

To make a long story short, Sam got into Bard on an early admission decision, and I got into Hampshire, but decided to defer for a year so that I could get a job to see what the real world was like for a while--or at least what it was like from my cozy room in my parents’ house, who didn’t charge me rent. I actually applied to Bard as well, but I like to think the fact that Sam had already decided to go there influenced my decision to go and do something else for once. (Or maybe it was the fact that our tour of Hampshire just happened to coincide with Danny DeVito and Rhea Pearlman’s visit with their son. That definitely made my decision easier).

[Henry the VIII plays]

I first met Bill Cranshaw when I went to pick my brother up to bring him home from his first year of college in May of 2007. I would get to know him much better when, in April of 2008, Sam and Bill, along with their friends Paul and Anneka rode their bikes from Bard across the Berkshires to come visit me at Hampshire. To be more precise, I should say that Sam was visiting me, but Bill was visiting his brother, whose name was also Sam, and who also attended Hampshire. To recap, I, Will, was attending Hampshire with Bill’s brother Sam, while my brother Sam was attending Bard with Sam’s brother Bill, which is close enough to Will. Sam and Bill were not twins; Sam Cranshaw was a few years older than Bill and Sam and me--and he was a really interesting person. He was an avid skateboarder, and had figured out a way to make skateboarding part of his senior project. Sam and Bill’s parents, Sue and Whitney Cranshaw, had also attended Hampshire back when it was founded. I think they were part of the first class of the early 1970s; Sue told me she worked in the bookstore with Ken Burns. I think Sam Cranshaw claimed to be the first second-generation Hampshire student whose parents had both attended, but I’m not sure how he could have verified that.

I’m not trying to say that this happened deliberately, but in hindsight, does it not seem strange that my brother Sam would gravitate towards, and eventually become the closest of friends with, a kid named Bill, or Will if you will, whose brother Sam attended the same school as his twin brother, Will? I know this isn’t the same thing as marrying a twin, but is this co-dependence losing its training wheels?

That bike trip from Bard to Hampshire was the first of many trips among my brother’s group of friends. After graduating from Bard, my brother actually came to Amherst and lived near me for a while. He got a job working at a warehouse. We went out to breakfast a lot during those months, the way we used to when we had paper routes back in Bethlehem, and spent most of our earnings in diners on Friday and Wednesday mornings. Sam found the time to run the Hartford Marathon one weekend, even though he didn’t really find the time to train for it. (He told me the most he did to train for it was to go on a 7-mile run one Saturday when he wasn’t working). But Sam was just biding his time. He was working and saving his money.

In the spring of 2011, Sam moved his stuff back to Bethlehem with our parents. Then he flew out to Orange County, California, to meet up with his friends Paul, Bill, and Hanna to embark on a cross-country bike trip. They made it as far as Circe, Arkansas.

I should probably mention that the other thing Sam started doing around the time he graduated from college was writing music. He sent me a tape during my last semester of college, and I was rather impressed with his songwriting. That was the first time I heard the song, “Someone Else’s Blues,” which is a song about being a twin.

[play verse]I remember being extremely impressed and maybe even a little bit jealous at what I was hearing. I think I always thought that writing music shouldn’t be that hard, especially if I knew how to play an instrument, which I did--the piano. But not well. [can you still play piano with an old worn out guitar]. But I never took the time to learn how to play the guitar--at least not until after my daughter was born. And at some point, I think anxiety set in, the way I imagine it sometimes can with siblings, and probably always does with twins. At a certain point I was crippled by the anxiety of influence, so I just stopped trying. Writing--and writing music--was Sam’s thing. I would have to figure something else out.

>Woody Allen: Those who can, do. Those who can’t, teach. Those who can’t teach, teach gym.

I actually would eventually become a teacher. But I feel like most of what I have learned, I have learned from Sam.

[return to audio of toast - stop at : fall apart]A few days before I graduated from college, I was eating with some friends at a burger place in Northampton, Massachusetts, when I got a call from my mom. Normally, I wouldn’t answer the phone if I was out, but I had missed a call from her earlier, so I picked it up. She told me she had gotten some sad news from Sam on the bike trip. I walked outside with my phone, and she told me that Bill had been hit by a car. “He didn’t make it,” she said. Those were the same words Sam said to me when I called him later that night, trying to find out what had happened, and how he was doing. “He didn’t make it."

I knew Sam was going to miss my college graduation, but now it wasn’t going to be because he was seeing the country, it was going to be because he was busy planning a memorial service. So, as soon as I was finished graduating from college, I drove with my parents the hundred miles to Bard to attend the memorial service for Bill Cranshaw, to be held on the following day.

I remember that I didn’t see my brother until later in the evening the night I arrived. He was standing in his friend’s apartment, surrounded by friends who were all drinking beer and making paper cranes. Some were laughing, some were crying. After I hugged my brother, someone put a beer in my hand, and someone else shoved some paper into my other, and insisted I start folding into the shape of an animal.

I remember spending that night with my brother in a gigantic chicken coop on a property belonging to someone he knew in Tivoli, which had been converted into a kind of apartment with a few beds. I remember him telling me that he hadn’t gotten much sleep in the last week since the accident, and that he was so tired of crying that he just couldn’t cry anymore. He also told me that Bill’s parents and brother were going to arrive the following morning from Colorado.

When we woke up the next morning, Sam had to run off on an errand to get ready for the service later that day. He told me I should walk into Tivoli and try to grab a donut from the bakery, and that we would meet up later.

Tivoli, New York, is very tiny. It has a fancy hotel restaurant, a bakery, a pizza shop, a laundromat, and that’s about it. As I was leaving the bakery, I saw Bill’s mom, dad, and brother walking down the street towards me. They had just arrived from the airport. I recognized them immediately. I had only met Bill’s parents once before at Sam’s graduation the year before, but I remember that I had pressed them for stories of what Hampshire was like in the early days.

Twins get used to being mistaken for one another. You also get used to having people embarrass themselves the first time they meet the other sibling, and can finally make a comparison up close. Our own mother calls us by the wrong name every now and then. In my toast at my brother’s wedding, I wasn’t kidding when I said that people had been coming up to me all weekend and congratulating me. There were a lot of plus-ones at the wedding who had neve met Sam, and who just assumed I was him. I remember letting one guy get pretty confused before I corrected him--he saw me playing with my two-year old son and started asking me questions about whether this was my second marriage already. No, friend. I’m the groom’s twin brother. If you’re a twin, you get used to this sort of thing.

But I don’t think I was ready for the way Bill’s mom greeted me. When I got close enough to her on that vacant Tivoli sidewalk on that foggy, cool May morning, Sue, Bill’s mom, opened her arms and grabbed me. “Oh, Sam!” she whimpered. As I held her, I could feel her body get heavier with each sob. And I slowly realized the weight I was bearing. Normally, when people mistake me for my brother, I’m pretty quick to correct them and laugh it off. But I couldn’t move. Sue had identified me. “Oh Sam.”

This is the moment that has haunted me. It’s when I realized, wow, I’m really not my brother. It’s when I realized I don’t think I can handle the responsibility of being my brother. Because this was a tremendous weight. I remember thinking that Sam’s reunion with Sue and Whitney had to be special. I don’t know who had called them to tell them that their son was dead, but I think Sam had spoken with them at some point to tell them his version of what had happened. And now, I had interrupted the sanctity of that reunion, simply by being in the wrong place at the wrong time. I felt like I had deceived Bill’s mom by wearing my brother’s face, posture, and gait on the morning of her son’s funeral. I remember thinking that Sue deserved to hug my brother, who had been there with her son when he died, who had shared in her loss for the way he had been unable to do anything to save him.

In the time I have had to reflect on that moment, it has also occurred to me that maybe Sue hadn’t mistaken me at all, but that maybe she couldn’t bring herself to call me by my name--because I bore the name of her dead son. Or maybe she had been busy consoling her other son over the past several days, and had just gotten used to saying, “Oh, Sam!” It’s not her fault that she named her sons Bill and Sam.

I didn’t know what it was like to be too tired to cry. And I couldn’t stop crying as my brother read his eulogy for Bill later that afternoon. I remember thinking that my twin brother had suddenly grown old, become in an instant decades my senior. I remember thinking that we weren’t twins anymore, that something had happened here that was irreparable. I also remember thinking that it just as easily could have been Sam who had been killed.

Did you catch that?

“Like you, I only wanted someone that I could save. So that if I am nothing but a coward now, and you may not believe this, and you do not have to, it is only because I was once much too brave.”

As I mentioned in my toast, I try to go and hear my brother play music whenever I can. It’s not often; I live and work in Western Massachusetts, and my brother lives and works in Philadelphia. And even if I don’t always get to sit up front, I do think there is something about hearing him live that doesn’t always translate well on recording. I wasn’t able to make it to the show where Sam first performed this song, which might be somewhat pretentiously titled, “A Brief Reflection Upon My Life to Date.” For all I know, this is the only time he ever performed this song. (And that’s the thing about being a prolific songwriter; Sam is always writing new music, so I often don’t get to see him perform some of my favorite songs more than once, because he’s always got new songs ready to go.) The song feels a bit like a journal entry. There is no catchy refrain, no sparkling melody; it’s just the same three cords strummed over and over again against a desultory reflection. But this is one of my favorite songs by my brother because of that line. Once, I was much too brave. You expect a brag--you may not believe this, and you do not have to--and then he punches you in the gut with that. Once, I was much too brave.

Stop music [He was a friend of mine]In the months following Bill’s memorial service, Sam moved back home to Bethlehem for a while, then he moved to Nashville--no, not to make it big as a musician, though I don’t think the move hurt him any in that department--but to attend a graduate program at Vanderbilt Divinity School. I spent the rest of the summer in Western Mass, and then started a graduate program of my own at Umass Amherst. But during those months, every now and then my brother would send me a handwritten letter and a burned CD of some of his songs. The recordings were often pretty crude--laden with white noise. I couldn’t tell if that was deliberate on his part--maybe trying to imitate the hastily-made recordings of Woody Guthrie. Or maybe he was just using some primitive equipment. In a lot of my brother’s songs from that period, I don’t get the sense that he really wanted his audience to think of him as a good singer. Sometimes, I felt like I was his audience--that his music wouldn’t make sense to anyone else but me or those who were there at Bill’s funeral.

I don’t know what it’s like to be much too brave. I don’t know what it’s like to watch your best friend--who wasn’t doing anything wrong, by the way, who was in the shoulder, wearing his helmet, minding the traffic, watching his speed--suddenly get hit by a car. I don’t know what it’s like to try to find the courage to attempt CPR without really knowing how it’s done. I don’t even know what it’s like to have to wait for an ambulance, or to have to read the faces of the EMTs who can tell when someone is revivable, and when they’re not. I don’t know what it’s like to lose a brother, a son, or even a best friend.

But I felt like a lot of the songs my brother sent me during that period were an attempt to convey what it was like. Some of them may have even told me that the Sam I had said goodbye to had left with Bill and had never come back.

Take, for instance, Right Where We Left Off, a song that breaks my heart every time I listen to it. Sam made a cleaner recording of this song, but the original recording he sent me, which sounds like it was recorded on a disintegrating tape. For a long time, I couldn’t listen to this song without crying. It’s the only song of my brother’s that seems to address Bill directly. But it also reminds me that my brother and I were once able to pick up right where we left off, something it has become increasingly difficult to do.

Bill figures prominently in some of Sam’s songs. Like “Say When,” a song whose title always reminds me of how my dad used to pour milk on my cereal when I was too young to do it myself, and would ask us to “Say when.” Instead of saying “stop,” we always just said, “When.” And in a way, that is what it’s about; say when once you’ve had enough. And even though he keeps saying when, he doesn’t get to control his trauma or decide when his grief is through with him.

[he was my friend]Bill definitely seems like one of the geese in “Two Geese,” whose only purpose is to remind the narrator of an unnamed “you.” [Intro to song] Something ‘bout the way those two geese flew, reminded me of you. [perhaps it was the way they stayed in stride] or [I got to my legs...]

And then at other times, Bill makes a much more subtle appearance in Sam’s music. Take, In No Hurry Now, a song about taking it easy when things seem like they’re getting out of hand. [I had a best friends he had a crash].

[Shakespeare toast?]At Sam’s wedding, Jimil’s half-brother West came up to me after my toast and asked me what I was talking about when I referenced May 2011 in my speech. (Sue, Whitney, and Sam were there for my toast; they had made it to the wedding. Whitney, who’s an entomologist, actually caused a traffic jam on his way up the one narrow road that climbs the mountain to the Bogus Basin resort. He pulled over--thought apparently not far enough for traffic to pass--to get a look at a rare beetle. This is considered normal behavior for Whitney, even for a wedding.) And as I explained everything to West, I found myself wondering how other people listen to Sam’s music who don’t know his story.

Part of me feels like I’m breaking a rule by sharing this with you--that I’m talking over the music, shouting its meaning at you instead of letting the artist speak for himself, or the artwork speak for itself. I get that it sounds like I’m committing a cardinal sin for an English professor, who’s supposed to know that the author is dead and all that. But I’m also trying to explain what it is like to be a twin, and to watch your twin experience something traumatic that you can’t, for once, share. Sam has communicated his trauma to me and to others through his music. I, on the other hand, have not been good at reciprocating or communicating my sympathy and my empathy to my brother over the years. In graduate school, my habit of writing to my brother fell to the wayside, and getting married without telling him didn’t really help to make things any better. I have, however, made use of other aspects of our supposed twin language. As I explained in my toast, I have had a habit of imitating Sam over the years; I think this is something twins do. They find their individuality, their independence, their solitude in one another.

Two years after Sam started his graduate program in Nashville, he received his MA from Vanderbilt Divinity School. Our entire family went to his graduation ceremony, and Sam received an MTS--a Master’s in Theological Studies, a degree only slightly less useless than a Master’s in English. When my family and girlfriend (who would eventually become my wife) attended his graduation, we got to meet a lot of his friends and see how his music had only been nourished by his time in Nashville. And then, two days after I got back to Western Mass from Nashville, I found myself imitating my brother again. No, I didn’t start writing music. Instead, I loaded up my bike with my friend Bob, and set out on a bike trip half-way across the country. When I was in Nashville, I knew I had to be home in time for our departure date, but I couldn’t bring myself to tell my brother. I couldn’t bring myself to tell my family. I just didn’t want them to worry or to give me some speech about how I didn’t know what could happen out there. I knew what could happen. That was the point. So without saying a word to my brother, I hopped on my bike and started riding.

So what happened on my bike trip?

Next time, on Someone Else’s Blues.

Someone Else’s Blues is a podcast written, produced, and edited by Will Steffen. Music, of course, by Sam Steffen.

By the way, if you like the music you have been hearing on this podcast, you can hear more at samsteffen.bandcamp.com. That’s SAMSTEFFEN.bandcamp.com.

Featured Music:

[Music]

SOMEONE ELSE’S BLUES: A PODCAST by Will Steffen EPISODE 2: “Death Was Out Riding His Horse In The Desert…” (Click here ——> xxxxx To Listen) Featured Music: “Makin’ It Up” “The Restless Wanderer’s Lullaby” - Album: Sam Steffen “Someone Else’s Blues” - Album: Someone Else’s Blues“ I Ain’t Even Had My Coffee Yet” - Album: Words, Words, Words “Hell of a Day I’m Havin’” Album: Since You Been Gone “Only Human” - Album: Only Human “The Ballad of William Tell” “Stuck” - Album: Wet Match “Since You Left (Ain’t Nothin’ Been the Same)” - Album: Since You Been Gone Episode 2: Death was out riding his horse in the desert On the last episode of Someone Else’s Blues, I introduced you to my twin brother Sam. I told you about Bill Crenshaw, Sam’s best friend from college, who died tragically while riding his bike across the country with my brother and their friends. I told you about how Bill’s mom briefly and accidentally mistook me for my brother at her son’s memorial service, and how it forever changed the way I would see my brother and think about our relationship. I also told you about how Sam started writing music to heal from his loss, and to remember his friend. I told you about how I hurt my brother (without meaning to), and then how I tried to redeem myself at his wedding, where he married another identical twin. And I told you how, almost exactly two years after Bill was killed, I started out on a cross country bike journey of my own. [Music stops] Whenever I hear people say that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, I always want to tell them how Webster’s dictionary defines cliche. I don’t like to think of myself as a copycat, but I also think that being a twin has turned my entire identity into a gimmick: just do what Sam does. But don’t do it in front of Sam. Do it in front of other people. Do it in front of people who don’t know Sam, or who don’t know you’re a twin. When I was in college, I started writing letters in longhand to some of my friends because this was something I noticed Sam doing with his friends, and something Sam and I had been doing for a while. It was a difficult habit to maintain, and I never felt like I was really saying what I wanted to say--which was maybe that I was pretending to be interested in something that I wasn’t, or that I was trying to appear like a disciplined and tortured intellectual, who was so tormented by the technological innovations of the modern world that he could hardly bear to drive in a car or to own fewer than three manual typewriters. Today, I think of that torment as “privilege,” and I usually just call these people hipsters. More times than not, my writing of letters to friends actually got me in a good bit of trouble and may have even cost me a friend or two. I think in longhand, intimacy is easy to mistake for, well, intimacy, when a brief hello is all that was ever due. My mistake was thinking that I could talk to other people the way I could talk to my brother. There were a number of things I imitated about my brother in high school. (Mind you, there were some things I wasn’t brave enough to do, either). [Bong sound effect?] I jumped off a bridge into the Lehigh river one time, but only because Sam did it first. I started swimming in the Monacacy creek too, following Sam’s example. The Monacacy is a sad, shallow, and probably carcinogenic body of water that runs through downtown Bethlehem. I started running cross country. Sometimes, instead of going for an eight-mile run, we would just run a half-mile down the Monacacy and jump in. Or have a snowball fight if it was cold. One time, we jumped into the Monocacy in January, and then spent the afternoon running around like wild people trying to get ourselves warm until our mom came and picked us up, looking disappointed and embarrassed. I eventually quit cross country--but only because Sam did first. I started getting interested in poetry and fiction, largely because Sam did. I also remember that I started reading Shakespeare--outside of class, mind you--because my brother took a lead role in the Shakespeare club. By the way, in September of 2018, I earned my doctorate. My dissertation was called, “Globalizing Nature on the Shakespearean Stage.” So yeah, I kept reading Shakespeare. As a twin, I’m not sure if you’re ever really free from the curse of imitation. I like to think I did these things that my brother did not because my brother did them, but because I wanted to do them, because I was interested in them. But then again, I like riding my bike because I grew up doing that with my brother. I enjoyed running a lot more when I was younger, before I had this sick dad-bod--but maybe it’s because I was running through a construction site or across a private golf course with my brother, trying to make trouble as quickly as I could avoid it. I like to think I wanted to ride my bike across the country just because I wanted to, but I can’t let go of the idea that I needed to do it because Sam did it first... Or tried to. [1. What did we have with us?; gear, journaling, raingear: Start w/ Will: “Do you remember a list of things we had with us?...Start w/ Bob: “I felt like I did a lot of thinking and planning, but then when it came time to leave, I just threw some stuff together…”; “I remember you were always writing in that journal, which I appreciate, because that journal is phenomenal to read…”] I did keep a journal of our journey together, but again, I think it was only because I had heard a rumor that my brother had documented his travels first, even though I had not read his journal at that point. But while he was on the road, I remember imagining him sleeplessly documenting the lightest breeze, or perhaps the briefest encounter with a stranger, while his companions slept, recharging their batteries. In looking back over my journal documenting the adventure I had during the summer of 2013 with my friend Bob, I think it is clear that I had one central question in mind on our trip: why are we doing this? On Wednesday, May 15, 2013, my pal Bob Gruber and I set out on our bikes from our apartment on Cherry Street in Northampton, Massachusetts. On Saturday, June 1, 2013, we arrived at our destination in Appleton, Wisconsin, the place Bob called home, a distance of more than 1,100 miles. From there, I would fly off to LA to live with my girlfriend, Anna--who is now my wife--for the remainder of the summer. And in a few weeks, Bob would fly right back to Western Massachusetts, where he had a summer job waiting for him. So why did we do it? Why do this, knowing what could go wrong? Knowing that almost everything was at stake? [Intro music] My name is Will Steffen. Welcome to Someone Else’s Blues, a podcast about twins, twinship, and the best singer-songwriter you’ve never heard of. Part 2: Death Was Out Riding His Horse In The Desert Imitation is one answer to the question, why go on a long-distance bike trip?--it’s a simple answer. A convenient answer. But another answer is that it really gave me a chance to get to know my travelling companion, Bob Gruber. Bob and I had been roommates for about a year when we set off, but I learned things about Bob on the road that I never would have learned simply sharing a bathroom and a kitchen with him. I first met Bob at a UMass Graduate Student Mixer at a bar in Amherst Massachusetts. The whole point was that you were supposed to meet other graduate students in other programs. It was our first week as grad students, and we were both feeling pretty intimidated. But I don’t think I have ever made such a good friend so fast. Bob was getting started on his PhD coursework in Philosophy; I was studying English (with a concentration on the early modern stage). [play audio - it was kind of like a first date; I laughed when I heard your name was Bob. Start with Bob: “Yeah I don’t remember going anywhere afterwards…” play to end of clip] [Intro music/ Bob’s Theme: I ain’t even had my coffee yet/ Hell of a Day I’m Having] On our bike trip, I tried to keep track of all the weird things I was discovering about this person that I thought I already knew. On the third day of our trip, Bob was asking Jeff--our warmshowers host in Schenectady, New York--what it was like to be an engineer. Bob said, “Engineering, huh? You know, I took a couple of engineering courses in college. And then I thought, ‘This is way too practical for me. I think I’m gonna stick with philosophy.’” At the time, I found this funny because I thought that bicycling across the country was perhaps one of the least practical things I could think of doing. “I am still struggling to articulate just why it is I am out here,” I wrote in my journal. “Tonight, in Ilion, New York. I think love has something to do with it—for Bob, for Anna, for my brothers, and even for my parents. But what the hell is practical about love? There is a thing full of design flaws. When Bob and I reached Ilion, New York, we stayed with his aunt Mary-Alice and uncle Bill. Mary-Alice used to teach elementary school, and she is the one who told me about something called “the Gruber curse,” where members of the Gruber family cannot let something be if it is just a little to the side, or a little off the mark. As Bob’s dad David would later explain it to me, “There are only two ways to do something. There’s the wrong way, and then there’s the Gruber way.” “I guess I haven’t noticed this curse being manifested in Bob,” I wrote that night in Ilion, “but I also didn’t know such a curse existed.” The next day, outside of a place called Rome, New York, I learned what Mary-Alice was talking about. Here’s what I wrote the following night: We got two flats today. Well, four. Well, Bob got two, which means that he is averaging—or we are averaging?—one a day. The first was on our way into Rome, where all roads lead. A piece of glass had lodged itself in Bob’s tire, and punctured the tube. Bob’s tires, it seems, are a regular vacuum for glass shards. My tires are bald. I’m not sure any of our tires will last the trip. Anyway, Bob patched the tube while I removed glass from his tire. Then he pumped it up with his handy hand pump. “That’s full. That’ll do,” I told Bob. “I don’t want it to just do. I want it to be a good tire.” He pumped the tire a few more times. “That feels pretty rigid.” “One more ought to do it,” he said. With one more pump, Bob ripped the pump nozzle off, and tore the pin clean out of the valve, losing all of the air, and rendering the tube useless. So he wasted a patch, and used his last spare tube. [Play first verse of “Ain’t even had my coffee yet”] In Erie, Pennsylvania, I remember admiring Bob for burning a map that our host in Buffalo New York had given to us: We stopped at a grocery store for Gatorade and poptarts, I wrote. We then found the Blasco Memorial Library right on the lakefront in Erie, where we used the facilities, checked googlemaps, and even glanced at what maps were available to us there. We were without a map. Last night, in his effort to start what turned out to be a very comforting fire, Bob burned the map of New York that Cliff had given to us. I admire him greatly for being able to distance himself from what he has only had to pass through to get where he is now—to do away with the tools which have gotten him where he is. Wouldn’t these pages do just as well in the fire as they would keeping my ink dry for me? [Pause] One of my favorite versions of Bob came out on day 12. We were in Fremont, Indiana. It was Sunday, May 26, 2013, the day before Memorial Day; we were trying to secure a campground on the eve of Memorial day, when everybody and their mother was out camping. As we hunted for a place to spend the night, a version of Bob reared its head which I’m not sure I had ever seen before, or since. It was Bob frustrated. Bob, interrupted. But it was also charming because of how agreeable he is, even when miffed: Camp Pokagan was full, I wrote. We biked six or seven miles out of Angola to a campsite that was full. The woman at the office gave us some alternatives. We each called a few. Bob told a woman at a site eight or nine miles back in Angola that we would be there by 8pm. Bob also wanted to go camp on the sly in the state park. I wanted to rest, but I did not want to backtrack either. I called a few places too, and found one a few more miles down the road. After beer and pizza, I certainly didn’t want to do any more biking, but the farther we went tonight, the less we would have to travel tomorrow, and I have a century planned for tomorrow. Eventually, Bob agreed to accompany me to a Jellystone resort three or four miles down the road. It took a lot of convincing, though. Bob is quite principled when it comes to camping. “My dad always says, ‘Never camp for more than thirty dollars. And don’t ever go to one of those Jellystone places.’ How much is it, anyway?” The woman on the phone had told me $49 for the night. “Fifty? No. No way. That’s like a new videogame. That’s Rollercoaster Tycoon Deluxe 3-D. Fifty bucks? That’s like a leatherbound copy of The Tempest with annotations from William Shakespeare himself!” As we biked to Jellystone, we kept our eyes open for a good free spot, but none presented itself. We even glanced longingly at the roof of a mini-mall, which was an idea I had proposed only half in jest. I know that Bob prefers to do what is legal over what is free, but he did seem brokenhearted about promising that woman at another campsite back in Angola that he and I were on our way to her. He called her back once we got to Jellystone; from the tone of his voice, I gathered that they would only ever be just friends, but even that did not seem likely anymore. Bob is making a fire now. He could have flirted with the girl at the registration counter a bit more, who seemed to swoon when he told her how far we had come. But he was too upset to notice, I think. Maybe it was how much we were paying. Maybe it was the phonecall. He barely noticed that she gave us a 10% discount for just travelling through; I am skeptical about whether such a discount actually exists. “I don’t care what the park is called,” Bob pouted, as we selected our campsite from the few left at the far end of the property, beyond the sea of Winnebegos and family campers, near the chain-link fence that was only a few feet from the highway. “I’m calling it Jellyville. It’s camping for the weak.” [audio of “BOb’s anxiety, Will’s anxiety, dangerous rides, Bill, Casey”; Start with: “I think you know this about me that I’m generally an optimist…”; “I was scared on that day…” “It’s so nice to know that you can bike through New York… (Insert New York reflections here!) “I never really worried for my safety, or that night I described with that tree” “I don’t know if you knew how anxious I was for a lot of that trip...I don’t even know if you told me about Bill… Will invited himself” END: “I didn’t want to do it alone.”] When we finished the trip I spent a few days in Appleton with Bob. I still don’t think I made the best impression on Bob’s parents, who are two of the nicest people I have ever met. I remember Bob’s dad handing me a beer in the driveway after we arrived. The next day, Bob’s mom invited us to come in and speak to her elementary school class about our trip, which they had been tracking on this map that they had hung up in their room. She had somehow attached a photo of us on our bikes to a popsicle stick, and she moved it Westward along the map each day that she was updated on our whereabouts. I remember feeling like a superhero walking into that classroom. Bob and I dressed in our bike shorts and wore our helmets to give us some credibility, and then we gave a little presentation on how to practice bike safety. We also fielded some hilarious questions from the students. One girl raised her hand and asked, “Were there any awkward silences?” Bob and I just laughed at her. Another student asked, “Where was the strangest place you brushed your teeth?” I had my answer prepared. “Movie theater drinking fountain.” Bob and I were pretty exhausted when we arrived in Appleton, and we were eager to relax. Somehow, I convinced Bob that we needed to rent all 5 of the Fast and the Furious movies from his video store and watch them all in quick succession. (I know right? There were still video stores in Appleton in 2013!) We had just seen the sixth one a few days before when we stayed with my friends Joe and Emma in New Buffalo, Michigan, but Bob didn’t understand how the Rock could have been the adversary in the last film if he was working with Dom and Brian in the sixth one. He didn’t understand the formula--that you have to be against the family before you can be part of the family; and he didn’t share my hope that, if Letty could come back, then maybe Han could too… But it’s true that Bob probably wasn’t aware of how anxious I was during our trip. On our first day, we rode 51 miles from Northampton MA to New Lebanon, just over the border in New York. It was a relatively brief day of riding, but riding in the Berkshires with all of our gear proved pretty exhausting. But I also had time to generate a more substantial journal entry during the first night. Here’s what I wrote: Today is Bob’s birthday. May 15. Tomorrow marks the two-year anniversary of the death of my friend Bill Cranshaw. On May 16, 2011, Bill was struck by a car and killed while riding his bike through Arkansas during a cross-country bike trip that he had begun forty-five days earlier in Irvine, CA, with three of his best friends from college, including my twin brother. Bill has been on my mind a great deal lately, as this day has been approaching. I have been reluctant to tell people of my plan to bike part of the way across the country with my roommate, Bob, for precisely this reason—that I am deeply suspicious of what lies waiting for each of us in the road. I have yet to tell my family that I have already hit the road because I am afraid of what their reaction will be—though I have every intention of emailing them before the day is through and confessing everything. I anticipate nothing but objections from my father, a reluctant support from my mother, and hilarious advice from my elder brother. From Sam, who is today in Santa Fe at a reunion with several of his friends from Bard who shared Bill’s friendship and its loss, I can imagine a warm, “Be careful,” as easily as I can imagine him advising me defiantly to turn around and go back. But I left this morning with a deep breath and an exhale that fostered the understanding that Death lies waiting for me in the road, though I do not know upon which turn or upon which day it shall be my misfortune to meet him. I left this morning knowing that Bill did not do a damn thing wrong—that he died on a beautiful day under a willow tree in a ditch on the side of the road somewhere in Arkansas. There’s a divinity that shapes our ends, rough hew them how we will. ...Tonight, we are staying with someone called Eli in a place named New Lebanon, New York. We found Eli through warmshowers.org, a wonderful online biking network which we shall be relying on heavily for the duration of our trip. Before unfolding the details of our journey today—which I am happy to say we have completed safely by midafternoon—I should like to attempt to compose a brief statement of purpose for why I am keeping such a detailed record of my travel with Bob, especially when my attempts to describe these events in my rude vernacular should perhaps prove meaningless to anyone who does not plan to take up a similar journey, following a similar route by the similar means of bicycling. And I should like to clarify that my purpose is multifold. Anna-Claire, my beloved girlfriend, is perhaps the primary reason for my putting down here what might otherwise pass as all things must. (I go on to explain how I planned to give my journal to Anna to make up for the many times I neglected to call her, either because of bad reception, or else because I simply didn’t want to talk on the phone).... Perhaps too, it is my intention to forge a closer relationship with my brother with this document. Sam does not write to me as often as he used to. There is no doubt in my mind that he departed on his cross-country bike trip one person, and came back another—just as there is no doubt in my mind that I left Northampton this morning one person, but shall return another. The degree to which I alter shall be determined in the road… [Music starts] One of my favorite songs by my brother, the eponymous track on his album, Only Human, starts with a verse about two men out riding in a desert when they are met suddenly by Death. [play first verse of Only Human] I’m not sure when Sam wrote this song--I only heard it for the first time a few years ago--but I feel like this verse captures the sentiment of what I was feeling out there in the road. The whole Oedipus-met-his-fate-on-the-path-he-took-to-avoid-it speech that I give to my students every semester when I teach Western World Literature. Every day that I woke up, I would ask myself, “Is this the day I’m gonna eat it? Or, Is this the day that I’m gonna have to call Bob’s parents?” When I saw the map that Bob’s mom had created for her kindergarten students, I remember thinking, “Thank God she didn’t have to tell these kids that one of us was dead.” And I remember realizing then that not everyone was thinking about this trip in the same way that I was. I mean, how could they? [audio- Jeff; Warmshowers hospitality, engagement is off; he was a phenomenal host; they were all excellent… Start: Bob: But perhaps most notable about this guy was his collection of empty hotsauce bottles… They were all excellent...] I made this recording with Bob on April 2, 2020 while I was visiting my parents in Bethlehem Pennsylvania. I was actually helping my dad out, who had just broken his hip a few days before. I figured a phone call was appropriate, since I couldn’t be sure when I would actually get to see Bob in person next. Starting a podcast is a great way to kill time in quarantine during the coronavirus. I asked Bob a few questions about our trip--about his favorite days of riding, his favorite hosts. Bob and I keep referring to our “hosts” because we took advantage of a wonderful online tool in the biking community--something I had learned about from my brother and his trip--called “warmshowers.” It’s basically a version of couch-surfer.com for cyclists who are touring. All of our warmshowers hosts--Eli in New Lebanon, Jeff in Schenectady, Jenny and Olin in Syracuse, Cliff in Buffalo, Dave and Mary in Wakeman, Ohio were active in the biking community. They had stories of their own to tell us about their tours, and food to give us, perhaps in remembrance of when they had dismounted, hungry and tired, at the hovel of a stranger who offered them something similar. Even Jack, our host in Perrysburg Ohio, who we never met, but who let us pitch a tent in his backyard anyway, was extremely hospitable in his absence. I don’t remember anyone telling us a story as tragic as the one that I carried with me of my brother’s ill-fated trip, and I don’t remember sharing it with anyone. But I remember being introduced, slowly, gradually, to a version of reality where a bike tour didn’t have to end in ruin. Jeff was our host in Schenectady, New York, on our second night of the trip. Here’s what I wrote about him: I should really give you a description of Jeff’s bike before introducing the man himself. He has a GT with a fancy speedometer on it. The most striking feature of his bike is the action figure he has tied to his brakelines at the helm of his ship. He told me it is a character from a sci-fi show—Galaxy Voyager? I can’t remember what the show was called, actually—whose epithet in the show is “the best travelling companion in the universe.” Right before we left the train station, Jeff found a Coke bottle cap on the ground with some sort of code written on the inside, which I guess can still be redeemed for points and prizes online. Anyway, Jeff picked it up and brushed it off. “Sweet,” he muttered, putting it into his pocket. Jeff is a civil engineer. I enjoyed listening to his narrative of the bikeway as we biked it; he is actually on of the bikeway patrollers—one of the people responsible for the bikeway, or at least the part that stretches through Schenectady. What a treat to hear all of the ins and outs of the bikeway’s ten-mile stretch from the train station to Jeff’s third story apartment in downtown Schenectady. He pointed out spelling errors—the “yeild” sign. He commented on every misplaced or pointless stop sign, the design flaw where you actually have to ride over the curb to cross the street because of a misplaced water grate. The ill-fashioned steep gravel hill with the sharp turns was the most helpful to learn about before experiencing. He also told us of where improvement was badly needed; he gave us the narrative of a crosswalk where someone was hit by a car and “eventually killed” a few years back because traffic speeds around a dangerous curve without warning of the impending bike crossing. “They eventually took him off life support. They definitely need some lights or something here.” At one point, we came to a downed tree limb. Jeff stopped and pulled out his pocket knife. He used his miniature saw to trim the branches. Eventually, we pulled it down and off to the side of the path. Jeff has hosted about sixteen people on warmshowers this year, including a pair last night bound for Niagra. To him, Bob and I are masochists, or westward-bound—riding into the headwind. To us, he is a godsend. Jeff’s apartment is perhaps what one would expect from a civil engineer—but what does that even mean? Star Trek and Simpsons DVD boxsets surround the livingroom. He offered Bob and me the futon, with sheets on it that had been used and not changed since the guests had stayed the night before. I think I will take a bed over a floor anytime. He also has a shelf dedicated to nothing but empty jars of salsa and hot sauce. I am afraid to ask him about it, and perhaps prefer the mystery. I would like to think his answer might be, “What? You don’t have a shelf of empty salsa and hot sauce jars? Pathetic.” On the following day, I continued: Last night for dinner, Jeff took us to Bombers, a burrito bar down the street from his apartment. Before we left, he grabbed a hot sauce bottle from one of his shelves. This one had hot sauce in it. “The secret to hot sauce,” he told us, “is that it ages. It ages well.” Jeff doesn’t open his hot sauces until a year after he buys them. After dinner, Jeff took us on a walking tour of the historic district of Schenectady; he carried that bottle of hot sauce with him the whole time. Jeff is extremely frustrated with a lot of the engineering of Schenectady; he pointed out several more design flaws to us—the superfluous traffic light facing the wrong way down a one-way street; the grate that fails to drain water properly on account of it is on the top of a hill. The thing I appreciated most about Jeff was that he was able to show us the world through his eyes. A tour of historical Schenectady for him is more about why the city requires more signs, or why a pedestrian walk button is no longer pushable. Although he did point some funny things out to us—like a plaque on the side of a building that read, “On this spot in 1896, nothing happened,” and the sandwich shop where Jeff gets a week’s supply of meat by ordering a single sandwich—by the end of the tour, I became worried about whether or not Jeff was actually happy with his life as an engineer in Schenectady. But I quickly realized that biking is his way of dealing with his frustrations. It seems he bikes away from Schenectady as often as possible. When we got back to his apartment—which I learned was also an office building—Jeff waxed poetical about each of his four bicycles. He has a folding bike, an English antique that he takes very good care of, a road bike, and his efficient machine that he met us on. He told us of being “Subarued” by a woman pulling into a Stewart’s Shop, who cut him off and then stopped, throwing him off of his bike directly onto his helmet, which broke in just about every place it was supposed to. He showed it to us. He also showed us a trainhorn from an Amtrak train. At first, I thought it was some sort of art project. I thought it was what a devil’s penis might look like. It was five-pronged and made of steel. Jeff loves Amtrak trains. We thought he was kidding when, after Bob and I had each showered and were ready to get a bite to eat, Jeff told us he wanted to wait until 7:35 so that he could hear the train go by. But he wasn’t. That train is music to his ears. He transitioned from showing us his bikes to showing us his trains without missing a beat. Bob and I let his monologue go on, too tired to interrupt or remind him of how late it was getting. The vanity plate on his Saab says “AMTK207,” and I was not surprised to see this morning that his email address—which he left at the end of a very thoughtful letter for us, which explained how to navigate the canalway trail through the cities we would be encountering today—included the alias, “Amtrak207.” I wonder if disgruntled passengers ever contact him with questions about their luggage by mistake. Nonetheless, I was reassured about Jeff’s disposition in Schenectady when he assured both me and Bob that, “You have to do what makes you happy. As long as you do that, I don’t have a problem.” It was clear to me this morning that Jeff had shared with us a great deal of what brings him joy. He met us at one train station on the Erie Canal bikeway and brought us to another—the Amtrak station that is right across the street from his apartment. After discovering his letter to us this morning, which he had stayed up long into the night typing out for us, I was confident that Jeff genuinely cares about the biking community and has a deep investment in the safety of his fellow cyclists. He took sixteen warmshowers travellers into his home last year because he knows they will be safe with him. His letter to us was very helpful, and somewhat hilarious at some instances. He gave us a brief history lesson on a few sites we would be passing where historical tragedies had taken place—each one due to engineering design flaws. In his last paragraph, he warned us to watch out for both snakes and something called “canalligators.” Bob and I spent a good while this morning trying to figure out what such a creature might look like. I guessed it might have been a turtle, or perhaps a highwayman. At one point, we passed an octopus-like design on a paved section of the trail, where the roots of a nearby tree buckled the pavement and merited some brightly-colored caution paint; this could have been the animal he meant. Now, I am confident Jeff meant it as a metaphor, though I’m not yet sure what for. It has been almost seven years since Bob and I set out on our adventure. A lot has happened in that time. Bob got engaged, and has plans to get married this summer--but I guess that depends on where things are with the coronavirus by then. I got married in November of 2013, the same year we took that trip. My daughter Calliope was born in May of 2014, and Oscar came along in October of 2017. Bob and I both defended our dissertations, and somehow both managed to land faculty positions in Springfield, MA--though at different colleges. (He’s at Springfield College; I’m at AIC; Go Yellow Jackets!) And perhaps it is because my faculty position invites me to teach Homer to the students in my Western World Literature course, but I can’t help but think about my bike trip--and especially the part through New York--in a slightly different light now. For example, when one travels West through New York along the Erie Canal trail on bicycle, one gets the impression that they are heading home from something epic, or maybe that they are naieve about just how far they will have to travel in order to make it home again. No, we didn’t pass through Ithaca, New York; we blew past it, on to other shores and isles. Appleton was our destination, but it doesn’t hurt to think of Bob at the time as an Odysseus without a Penelope. In a way, it might help to explain what we were doing out there. There were days, I’m sure of it, we were channelling Tennyson: [Battle cry sound effect] It may be that the gulfs will wash us down: It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles, And see the great Achilles, whom we knew. Tho' much is taken, much abides; and tho' We are not now that strength which in old days Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are; One equal temper of heroic hearts, Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield. Or maybe that’s all just a bag of wind. If I remember correctly, we yielded at every stop sign, bent with every raindrop. Still, it’s fitting, in a way, that so many towns and cities in New York are named after places in ancient Greece. (We actually passed through a town called Greece on our seventh day of the trip.) After all, wasn’t I sailing through some paved Aegean, eating the wind, inhaling the Lotus in the breeze, deaf to the wailing of sirens urging us to stop, to turn back, to remember this trip could end in some monster’s maw as easily as in the back of some ambulance? Wasn’t I pushing onward with wax in my ears? After our second day, it wasn’t even a lie to say that we had come from Troy--Troy, New York, of course--where we had probably stopped to poop at a gas station--and so maybe it wasn’t a lie either to say that we had left Troy burning and in ruins. We spent our third night of the trip in a place called Ilion, and the fourth in Syracuse. When I teach The Odyssey to students in my Western World Literature course, I like to focus on Books 9 and 10, where Odysseus encounters the Cyclops, the Lotus eaters, Aeolus, the Leastrygonians, and Circe. These are all tales of how he narrowly escaped his doom, used his cunning to outwit his enemies, saved his men from certain death--until too many of them died for him really to have been much of a savior at all. In a way, Odysseus reaffirms his Greek identity against the obstacles that would keep his men from returning to their homes--the drug of the Lotus, the cannibal Laestrygonians. What is civil defines itself against what is barbaric. But I also like to use these encounters to teach my students about the ancient Greek concept of xenia, meaning “guest-friendship.” It is the idea of being hospitable, and being hospitable for its own sake. To the ancient Greeks, any human could potentially be a God, and you didn’t really want to find this out the hard way. The relationship is built upon an exchange of gifts. It is the reason Odysseus brings wine with him into Polyphemus’s myopic and swallowing cave--to present it to his host as a gift. In exchange for the wine, the Cyclops mocks this custom of offering a guest-gift in return by simply promising to eat Odysseus last. I think Warmshowers is a modern form of xenia. The only difference is, instead of repaying your host with a gift in return for the hospitality they have shown you, you are expected to simply be a good host to someone else in the future--to open your home to some weary traveller depending on the kindness of strangers. [audio: Syracuse, ws hospitality, more biking; Start at beginning of clipstop after “It was dark by the time we got there…” or “Then I’ll send them to Cliff; they can go do Teen Trekks or whatever…”] Cliff was another one of our favorite hosts. [Audio - Cliff, Teen Trekks, NAvigation - Entire clip] Cliff let us pitch our tent in his backyard--which was covered in dog shit, by the way. He also had an outdoor shower that we used, which was really nothing more than a hose with a showerhead on it. My favorite thing about Cliff was the way he talked. Once we were showered, Cliff tried to point us in the direction of food. He was going to have dinner ready for us, but we had arrived later than expected—around 8pm. In his words, he “gave up on” us. We asked him where we might get some authentic Buffalo wings; we figured we might as well do something historic in Buffalo, even if there was only about fifteen minutes of daylight left. Cliff, who talks pretty fast and who drops his R’s at the end of words, said, “Oh, Angobaw. You wanna go down to Angobaw. Walk down Porta past the traffic circle till you get to Main Street. Angobaw. Can’t miss it.” He convinced us to walk when he realized we didn’t have a U-lock. He seemed confident Buffalo would swallow our bikes if we tried to take them out, which didn’t make me feel any better about sleeping in a tent in his back yard. He walked us part of the way down Porter to his mother’s house, pointing out the architecture of the music hall and some of the houses. He told us Buffalo is shrinking in size, and that it felt weird to be living in a city that is actually getting smaller. Cliff studied architecture; he has a master’s from the University of Buffalo. He also has a son at SUNY Purchase who was at the time doing a 700-mile tour down the coast of California. Bob and I ordered 20 authentic Buffalo wings from the Anchor Bar at the corner of Porta and Main. They were great, though I suppose they were nothing to write home about either. They tasted like Buffalo wings. The menu has the whole story on it, which I didn’t finish reading, but which essentially boils down to a woman in 1964 frying up some chicken instead of putting them in soup. When we were halfway through our meal, Cliff showed up and sat down with us. He ordered a Guinness, and told us he drove so that we wouldn’t have to walk back. Cliff, I think I can safely say, was a lot like Jeff in that he was very concerned for our safety and general well-being—which I sincerely appreciate. In the morning, we met Carol, Cliff’s wife, who made us a huge breakfast of eggs and lots of toast, tea, coffee, and orange juice. The food was passed from the kitchen through the window onto the porch where we dined. Bob and I were suspicious about why they wanted us to stay out of their house at all cost, but we were content with our arrangement. Cliff gave us a map of New York, and encouraged us to think about working for him at Teen Trekkers this summer. He pointed us in the right direction and wished us well. He also promised he would write us a favorable recommendation on our warmshowers accounts, so that other hosts would be more inclined to welcoming us; his words were, “People should know you guys aren’t a bunch of wife-killers.” We didn’t encounter any Cyclops on our trip. No one tried to imprison us, eat us, or turn us into pigs. But like Odysseus, I tried to be on guard about our hosts and other hazards--to watch out for potholes yawning like Charybdis. Nor do I think that my caution was unwarranted. After all, Bill had died in a place called Searcy. And while the town is named after a prominent nineteenth century legislator Richard Searcy--who spells his name SEARCY--as opposed to the bewitching queen of Aeaea, CIRCE--the homophone is enough to give me pause. Only one of Odysseus’s crew dies on Circe’s island, and his death is accidental. After a heavy night of drinking Elpenor falls asleep on the roof of Circe’s house, and when he wakes up, he accidentally stumbles to his doom. [What a hell of a day I’m having…] On the next episode of Someone Else’s Blues, Bob and I finish recounting our journey, I finally get in touch with my brother, and he sends me all 491 pages of his bike journal. And Sam revisits the theme of twins in another song about two brothers.

Featured Music:

[Music]